This article is the original version of my PKU mental health journey. Eventually, it inspired the creation of Never Give Up: A Rare Disease Podcast. And I turned it into a longer story. For the complete version of this story, please check out Regaining Hope: My Journey to Rare Disease Advocacy.

This is a story about hope. Believing in hope. Losing hope. Regaining hope. It’s about mental health—my mental health. I also happen to have a rare disease known as PKU. I’ve told my story of living with PKU before, many times. When I produced my video “My PKU Life” in 2011, I didn’t expect it to change my life. It certainly did. For over 10 years I’ve traveled the world speaking about my life with PKU, advocating for newborn screening, and producing videos about PKU. But I’ve never told this story, not completely.

I’ve been afraid—afraid of what others would think, and afraid that it would unleash memories that I’ve tried to bury. But, as I’ve learned, life has a way of bringing you to the moment you need to be, not where you want to be. There was a lot of discussion about mental health and PKU at the recently held National PKU Alliance Conference. It was refreshing to hear. I also realized that it was time for me to pause and reflect on my journey.

Broadcast Journalism in the Early 2000’s

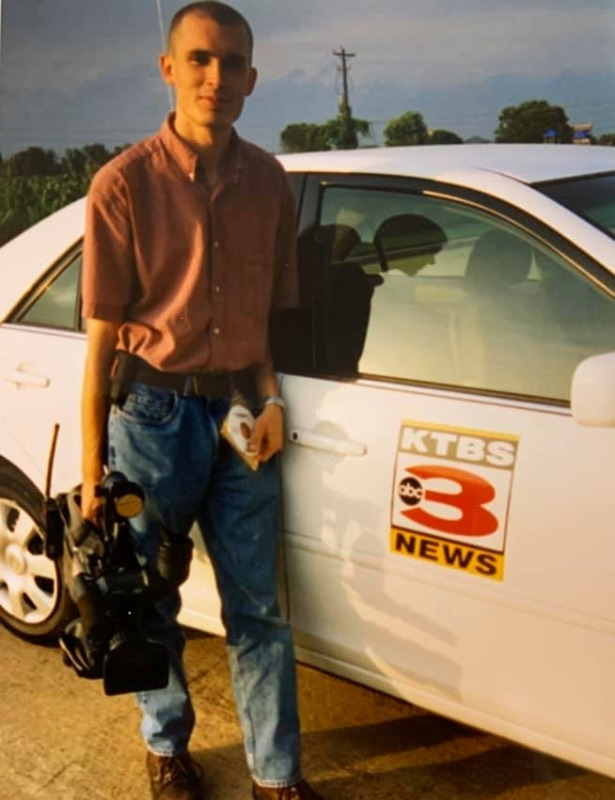

I was a TV Photojournalist in North Louisiana from 2001 to 2008. It’s easy to forget how different the world was 20 years ago. Social media didn’t exist. There was no YouTube. You could only get DVDs from Netflix; there was no streaming. You had to get your news the old-fashioned way: reading the newspaper, listening to the radio, or watching TV.

I never thought I’d work for a TV station. At the time, my plan was clear: I wanted to be a film director. But I met the love of my life, we got married when we were 20, and I needed a job. I was studying broadcast journalism in college. A job opened at our local NBC affiliate, and I took it. I thought it would be a great way for me to learn how to film and edit, but I didn’t think I would stay in journalism long. I also had no idea what I was getting myself into.

Although I was young, I had experienced some emotional pain. First, I had PKU. Living with PKU feels like a heavy weight, especially when you’re a teenager. Say that to anyone outside our community, and they don’t understand. But if you know, you know. But PKU isn’t the only factor in our lives. It certainly wasn’t in mine.

I had my first real encounter with how harsh the world can be when I was 18. My future step-sister was murdered. And I don’t know what else to say about that.

Six months after my wife and I were married, our apartment burned down. Thankfully, we were out of town at the time. Had we been at home, we likely wouldn’t have survived. I know all too well that an overnight fire can be fatal.

I remembered those life-altering events years later when I was covering homicides and fires. Another day at the office for me was someone else’s worst day of their life.

The Lifestyle of a TV Photojournalist

There are a variety of assignments, or beats, within journalism. Health, Politics, Crime, Weather – the list goes on and on. But when you’re a TV Photojournalist in a medium-sized market you cover it all. If it’s your on-call week then you’re on standby 24/7 in case anything happens overnight. Sometimes you don’t get a call all week, and sometimes you’re up all night most of the week. Naps become your best friend.

It was the best college job I could imagine. While other classmates were working in retail or restaurants, I was out each night chasing breaking news. On slow news days, especially when working nightside, I would jump in the news car, listen to the police & fire scanners, and wait for something to happen.

Something always happens. And when it did I’d try to be there as quickly as possible.

I spent a lot of time gathering news by myself. But I would also work with a reporter every day to turn a story. The pressure was intense.

Just finished shooting your story and only have 20 minutes to edit?

Get it done.

Just showed up to breaking news in the satellite truck and only have 10 minutes to set up and go live?

Get it done.

Never miss your slot.

It was a 24/7 adrenaline rush for 7 years. And I loved it.

It was fun, but it could also be surreal.

I didn’t grow up in South Louisiana, where hurricanes are common. So I was 21 before I rode out my first storm. Hurricane Isidore was expected to hit as a Category 3 storm. 70,000 people evacuated, but by the time it made landfall it weakened to a tropical storm. We rode it out in Golden Meadow, LA, and the next day we traveled all across South Louisiana surveying the damage and turning our story.

On February 1, 2003, I was on my way to work when I got a call from the News Director. Immediately, I knew some story was breaking. It was a Saturday morning, and a News Director in the newsroom on a Saturday morning meant something big was happening. Space Shuttle Columbia broke apart during reentry over our viewing area. A reporter and I were first out the door at our station, and we spent the day at Toledo Bend Reservoir, where numerous residents heard the sonic booms after it broke apart.

I once randomly interviewed a man for a story about depression during the holiday season. Six months later, he killed three people and was on the run for seven weeks. We searched the archives one night and found the interview we had filmed the previous winter. We had his face and voice on tape, so we sent it to America’s Most Wanted.

The Daily Grind of Covering News

It was exciting. I was still in college, and every single day I was amassing a lifetime’s worth of memories. But as time went on, it wore me down.

On any given day, anything could happen. There was no normal day. We had to be prepared for anything to happen, at any time, no matter what we were doing. MVA’s (Motor Vehicle Accidents). House fires. Shootings. Stabbings. Natural Disasters. Train Derailments. Plane crashes. Dead body discoveries. Missing children. Boating accidents. Prisoner escapes. Bank Robberies. Explosions.

Again… A normal day at the office for me was someone else’s worst day of their life.

One night I pulled up to an MVA. Eighteen-wheeler vs. mini-van. It was late, about 10 PM. No one was available to tell me what happened, so I immediately began filming. On one hand, you’re hyper-aware of your surroundings. At the same time, you’re in your own little world. You’re there to do a job, and you’re trying your best to maintain some emotional distance from what’s going on around you.

The damage to the mini-van was extensive. The front end of the vehicle was wedged underneath the trailer. I moved closer to get footage inside the vehicle. I was about 15 feet away, and because it was dark I couldn’t tell what I was looking at. I turned on the light that was mounted to my TV camera. And that’s when I saw her, the driver, still in the vehicle. She was dead.

Now that I saw her, I couldn’t unsee her. I knew she was someone’s daughter, someone’s partner, someone’s mother. And she wouldn’t be coming home that night.

Another night I was called out to cover an overturned 18-wheeler. I got the call at about 4 AM, threw on some clothes, grabbed my gear, and jumped in the car. As I approached the area, I couldn’t see anything— no semitrailer, no police or emergency lights, nothing. I called the overnight producer to clarify the location. The scanners were going off in the newsroom. There was a shooting, and I was a few blocks away.

I arrived before the police. The ambulance was on the scene and the paramedics were treating the victim. I was about 100 feet away on the sidewalk, and I began filming, my head on a swivel because the suspect had fled on foot just minutes before I arrived. A few moments later, police swarmed the scene and the crime scene tape was up. My camera was focused on the medics as they treated the victim. They loaded him in the ambulance. 30 minutes passed. The ambulance didn’t move. A few minutes later, the coroner arrived.

The detectives told me that he was with a group of friends that night at a nightclub, stopped to get fuel on the way home, and someone walked up and shot him. His friends and family arrived a little while later. Their grief was raw. I finished gathering what I needed for the story, went back to the station to edit, and then went home just as the sun was rising. A few hours later, I was in a large crowd. Everyone was celebrating life. And all I could think about was the man I had watched die that morning.

For me, these were normal, daily experiences. At first, it upsets you. Months pass, and you see more every day. You grow cold. Years pass, and now you’re numb. You can look at death, and feel nothing.

And then came Hurricane Katrina.

Hurricane Katrina

On August 29, 2005, I stood in the newsroom and watched live as the levees broke in New Orleans. I watched as helicopters broadcast the first images of a flooded city. And I watched as a helicopter flew over the Lake Pontchartrain bridge showing severe damage from the high winds. I didn’t know it at the time, but five days later I would be in a boat on that lake, driving under that bridge.

I had been covering the local angle. Even though the storm wouldn’t hit our area, we were focused on it for days. Evacuees were seeking shelter in North Louisiana. It consumed every newscast. One night, after my live shot at one of the shelters, the Managing Editor for our station called me into his office. The storm had finally hit a couple of days before. He told me they were sending me down to New Orleans.

“There are two things I need to tell you, and they’re non-negotiable,” he said. “First, get your tetanus shot and whatever else your doctor can think of. We have no idea what chemicals are in that water. And secondly, don’t do any cowboy stuff and get yourself killed.”

We left the next day. While we were driving, we contacted a source in New Orleans. Many, if not most, of the people who stayed in the city were poor and had no means to evacuate. But others were taking advantage of the situation. There was looting, automatic gun battles in the street, and rampant murder. It was chaos.

The storm had hit on Monday, and we arrived in Baton Rouge on Friday night. I don’t know why, and I don’t care, but someone made the decision for us to go to Lake Pontchartrain the next day and survey the residential damage along the coast. I was perfectly happy with that decision. I wasn’t eager to go into New Orleans yet.

Saturday, September 3. I was with a crew on Lake Pontchartrain who was conducting search and rescue operations. The day before, all day, they pulled corpses out of the water. On this day, we expected more of the same. We didn’t see any death that day, but we saw a lot of destruction. Katrina was my third hurricane, and I had covered tornadoes as well. I had seen destruction, but this was different. It looked like a massive bomb had detonated.

Catastrophic is just a word until you see something like this… and hear the stories of those who survived.

We met a couple who lost everything. As we walked into their home I turned on my light. Everything was soaked. Mud was caked on the walls, on the ceiling. The waters rose to the third level while this couple was trapped inside. The husband said they almost swam out the window. The waters receded before that was necessary. They were physically intact, but emotionally and mentally scarred. I don’t think I heard the wife utter one intelligible word. She was distraught.

Distraught… there’s another word that’s just a word until you meet someone who is so shaken that she can’t speak.

As we drove back across the lake, we passed by the bridge I had seen on TV earlier in the week. We drew closer, and I noticed an abandoned taxi. I couldn’t help but wonder what had happened to the driver. Did the vehicle break down? Were they able to flee in another car? Or was their corpse inside? I thought about it for a few minutes. But then I remembered we had to get the story on the air. And so we went back to the satellite truck. And I went back to work.

That was the first day of our coverage of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. We were there for a few more days. The unimaginable had already happened. The city had flooded. It was now virtually abandoned. And yet, nearly a week later, it still felt like anything could happen at any moment. It was chaos. No emergency services. Deserted streets. Silence. Hotel rooms were unavailable, so we slept on the floor in strangers’ houses.

On our last day there, a buddy and I got to some high ground on an I-10 overpass. We looked out over New Orleans, still trying to process what we saw. A fire burned somewhere in the distance. No firefighters, so it just burned. Helicopters filled the skies, searching for remaining survivors. The water was still high in parts of the city, but it was receding. It was an empty, mostly abandoned city.

Some experiences in life are so surreal that you know you’ll remember them forever. This was one of those moments. I remember Katrina every day. It fundamentally changed my view of the world. From that time on, nowhere felt safe. Anything could happen. I knew it because I had seen it.

Leaving Broadcast Journalism

I stayed at the TV station for a few more years, but by early 2008 I was exhausted. I decided to leave broadcasting for a marketing job. My last assignment was back in New Orleans for the LSU National Championship. I ran satellite uplinks for live shots on Canal Street. The next day I drove back to town and turned in my gear. The following day I was at the new job.

I was back in the “real” world. I had the first desk job of my life. And for a long time, I enjoyed a typical, suburban, sheltered life.

March 9, 2009. I know the date well because I wrote it in my journal that night. I came home frustrated about a conversation I had that day. I don’t take it well when people provide easy answers to life’s most difficult problems. It’s easy to say “Stay positive” when someone has been sheltered their entire life. But when you’ve worked in the field, and have seen life in the streets, people in tremendous pain, or dying, you see life differently. I told my wife, “They have no idea what I’ve been through!”

But I had never shared with her what I had seen in the field. I had learned how to compartmentalize to function in that environment. I kept what I saw each night to myself. I didn’t talk about it when I came home. But that night something ripped open. My two worlds collided. And I shared story, after story, after story. It felt like seven years of my life that I had stuffed inside just came back to the surface. I wasn’t just remembering it. I was reliving it.

But I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know who to talk to. I knew I needed help. I knew things weren’t right.

One night I went to dinner with friends. They could tell that something was wrong, but I was trying to keep it all inside. Anyone struggling with depression or anxiety knows how to keep up appearances so that people won’t ask that annoying question, “Are you OK?” “NO! I’m not OK!”, that’s what you want to say. But you also know that people often ask that question expecting to hear, “I’m fine! Everything’s fine!”

I kept it together until I got to my car, and then once I was finally alone, I broke down. I don’t cry often. But that night, I cried. Hard. Images were flashing through my mind, on endless repeat. While writing this article, I’ve deliberately avoided sharing anything too graphic. I’ve hinted at it, and struggled with how much to share. People don’t realize how much you see when working in the field. If you’re covering an MVA, or anything involving death, you see a lot that you can never put on TV, much less forget.

That night in the car, as I was breaking down, it just came out: “How could I?” I felt tremendous guilt. For every time I stood by, watching others in the worst pain of their lives, or in their last moments on earth, and did nothing to help. For every time I approached a family in trauma and, like a shallow opportunist, asked if they wanted to be on TV. For allowing myself to become so cold, calloused, and caustic.

But it wasn’t just the guilt that I was feeling. I was experiencing anxiety and depression. I wasn’t just hyperactive, I was hyper-vigilant – always on guard because nowhere felt safe. I was spiraling out of control.

Seeking Help

Eventually, I sought help. I found a therapist and told her my story. And I received a diagnosis: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). At first, I couldn’t accept that. I thought that PTSD was what people in combat experienced. Or first responders. But not journalists. But I couldn’t deny that the symptoms fit. I had experienced extended exposure to traumatic events. I was having nightmares. Flashbacks. My mood was significantly altered. I was exhibiting avoidance behaviors. I was hyper-vigilant.

Around this time I discovered the work of a journalist named Mike Walter. Mike had witnessed the plane hit the Pentagon on 9/11. He had recently produced a documentary called Breaking News, Breaking Down. When I watched it, I finally felt like I wasn’t alone. Other journalists had done what seemed impossible to others in our industry – admit they were human. They acknowledged that those who work in the field witness trauma regularly. Eventually, it can take its toll. That was especially true for those who covered a major historical event like 9/11. Or in my case, Hurricane Katrina.

I stopped fighting and accepted my diagnosis. I had lost hope that I could have a future without anxiety. Without depression. Without flashbacks. Without nightmares. But having a diagnosis gave birth to hope once more. I realized that I wasn’t alone and that others were facing similar battles. And I began the long road to recovery.

PKU and Newborn Screening Advocacy

About two years later, one night in November 2011, I turned on my camera and shared my story about living with PKU. I didn’t know if anyone would ever see it. I just wanted to tell a story about PKU, to use my skills for a cause I believed in.

It was an expression of hope. I had spent so much of my life feeling like I wasn’t guaranteed a future. I knew that every moment was fleeting. That anything could happen at any time. Before I began my recovery process, I felt that any action to try to make the world a better place was futile.

When all you see is trauma, day after day after day, pretty soon that’s all you can see. But my recovery was beginning to show me that, yes, bad things happen every day to good people. And one day it may happen to me. But until then, it’s OK to live my life. It’s OK to believe in something. It’s OK to look forward to a bright future.

So, that’s what was in my mind when I produced my video “My PKU Life.” And my life changed.

The following years were a blur. I started traveling and speaking about life with PKU and why newborn screening is essential. I went to Finland, Brazil, Australia, Germany, & all over the US. I spoke on Capitol Hill for the 50th anniversary of newborn screening. I threw myself into PKU and newborn screening advocacy. Because I had something to believe in.

I had witnessed the worst happen to other people daily for several years. I couldn’t help them. I felt powerless. But now I could finally do something to help others. My actions mattered. If I overcame my fear and used my voice to speak on behalf of others affected by PKU, I could make a difference. Advocacy was my way back from despair.

But, best of all, I became friends with others affected by PKU on social media. No one else knew about the battles I was fighting daily to maintain hope, but their hope and passion inspired me to keep going.

Two Worlds Collide

As the years passed, my struggles with PTSD became less intense. But, at any moment, it can creep up unexpectedly. When the pandemic hit it was like watching the unimaginable happen all over again, just like Katrina, only it happened over a longer period. I would check the news or social media and have a panic attack, so I had to take a break. I’ve only been active on Facebook again for the last couple of months.

But a very recent experience brought everything full circle. I was on vacation a few weeks ago and spent some writing in my journal about Hurricane Katrina and my previous life in broadcast journalism. I also read about PTSD for the first time in years. The DART Center for Journalism & Trauma is an incredible resource, both for journalists covering trauma and processing their own. I read an article called “Covering Trauma: Impact on Journalists”. It described my experience. Perfectly.

Later, I was in a presentation about PKU and mental health. I looked up on the screen at one point and saw the words “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder”. And it all hit me again. I had a panic attack. My chest tightened, I couldn’t breathe, and my hands trembled uncontrollably. I felt vulnerable like I hadn’t in years. It was like two worlds were colliding: my previous life as a journalist in the field and my current life as a PKU advocate.

The next few days were difficult. I had flashbacks. I was hyper-vigilant. I couldn’t sleep. I would stay up, late into the night, writing in my journal. I wrote over 70 pages that week. I would do my best to be sociable in public, but I would take frequent breaks to be alone, so I could just breathe.

But it’s what I needed. I’ve been running from the pain for a long time, but I finally realized it’s time to slow down and deal with it. I still compartmentalize, lock it away, and ignore it. So many journalists think it’s admitting weakness to say that life in the field can wear you down. I think it just makes you human.

I’m sharing this now because I know what it’s like to go through the battle of your life and feel alone. No one should have to feel that way. Everyone in the PKU community is fighting a battle. Parents fighting for their children. Teens trying to fit in despite always standing out. Adults coping with always feeling different. Our individual life experiences aren’t the same, but we share a common experience of living with PKU. That’s why we need each other. We need to hope together.

Hope for the Future

I’ve spent the last few years trying to run from it all again, trying to keep my painful past far away from the life I now try to live as a PKU advocate. But I can’t run anymore. It’s time for me to accept both realities.

Yes, I’ve lived through a lot of pain. And yes, there is hope for the future.

Life is about living within that tension. It’s about facing the darkest moments when you are terrified because that’s when you often discover who you are. But it’s also about embracing every single moment as a gift because that’s when you discover who you are becoming.

Leave a Reply