This is a story from PKU history. It’s about the impact of advocacy and the significant role it plays in the advancement of treatments for rare diseases, as exemplified by the story of Mary and Sheila Jones and their contribution to the treatment of Phenylketonuria (PKU).

A Story From PKU History: “When Are You Going To Treat My Child?”

What is advocacy? What does it mean to be an advocate?

This comes up from time to time in discussions with friends. Certainly, legislative advocacy is important. Many of us are involved in events like Rare Disease Week on Capitol Hill here in the United States. Or we serve non-profit organizations that are determined to affect change through legislative policy.

But that’s only one part of advocacy.

At heart, advocacy is just telling your story. It’s sharing your experiences in the hope that it will change your life, and perhaps change others as well.

But what do you do when you feel like no one is listening? Or if your rare disease population is so small that you don’t know anyone else affected by your condition?

Today, I want to tell you a story from my rare disease community. It happened in the earliest days of our history. When there weren’t many people diagnosed with Phenylketonuria, or PKU. When no treatment existed.

For those of you unfamiliar with PKU… it’s an inherited metabolic disorder that affects how our bodies process an amino acid found in protein called Phenylalanine. In our community, we commonly refer to the initial treatment as the “low-protein diet”. But really, it’s a Phenylalanine-restricted diet.

If levels of that amino acid build up in our bodies, then it crosses the blood/brain barrier and causes brain damage. The consequences are most severe in those undiagnosed… or late-diagnosed.

Today, most people living with PKU receive treatment after being diagnosed through newborn screening. And live healthy. Yes, we have our challenges. I talk about them frequently. But… we have treatment.

This is a story about the development of that initial treatment.

It’s the story of a determined mother who fought for that treatment for her child’s rare disease…

And it’s the story of her child, someone who could never communicate verbally, but whose life and experiences paved the way for everyone who came after her living with PKU.

We often think that progress is determined by “the great leaders of history” and ignore the contributions of ordinary people, like you and me.

But these two women… changed the world and had an impact not just on the PKU community, but on the future development of newborn screening and all of the progress we’ve seen in the world of rare diseases.

Sheila: Unlocking the Treatment for PKU

The stories I normally tell on this podcast are either from my life or those I’ve personally witnessed. But this episode is different.

I’ve relied on source material to tell this story, a book that I highly recommend. It’s called “Sheila: Unlocking the Treatment for PKU”, written by Professor Anne Green. Professor Green has a distinguished career as a paediatric clinical chemist in the UK National Health Service, and a career-long interest in PKU.

The book is published by Brewin Books and all proceeds go to Birmingham Children’s Hospital Charity, who funded the book’s production and own the copyright. The charity works to enhance the experience of children and their families who access services at the hospital.

So, when you buy the book you are supporting their work.

The story I’m telling is not exhaustive. It’s just meant to introduce you to these events.

So, support the charity. Buy the book. And learn about this fascinating chapter in the history of rare disease life.

European Society for PKU and Allied Disorders

There’s an organization I’ll mention throughout this story, and I want to take a moment to tell you more about it.

The European Society for PKU and Allied Disorders Treated as Phenylketonuria, or ESPKU, is a non-profit umbrella organization of about 41 national and regional associations from 31 countries.

The ESPKU monitors EU regulations and legislative initiatives, assesses their impact on patients with PKU, and actively lobbies for the best regulations for the European PKU community.

But it’s the annual conference where everyone joins together. Patients, parents, delegates of member organizations and other PKU associations from Europe and the world, as well as doctors and dietitians, join the meeting. And each group has their own dedicated sessions.

The ESPKU is best known for the European Guidelines for Phenylketonuria, International PKU Day, the Sheila Jones Award, and the PKU Travel Passport. For more information follow ESPKU on social media or visit their website, espku.org. And, be sure to check for the latest information about the next annual conference, which is held in a different country each year.

Also, if you’d like to get a glimpse of what the ESPKU annual conference is like, check out my episode called “Finding Your Rare Disease Community.” It was recorded on location at the 2023 conference in Birmingham, UK.

And, it’s a reminder that no matter where we live in the world, or what rare disease affects us… When we come together we realize that we are not alone.

Photos from the 2023 ESPKU Conference in Birmingham, UK. I produced two episodes of Never Give Up: A Rare Disease Podcast from the event—“Finding Your Rare Disease Community” and “One Global Community: A Vision for the PKU Community”.

Learning About PKU History

I was standing in the back of the room, leaning against the wall. No amount of coffee or tea was helping my jet lag.

I had left the United States on Tuesday evening, arrived in the United Kingdom late Wednesday—without my luggage—and settled into my hotel room in Birmingham. It was now Friday, I still had no luggage, I was still trying to adjust to the six-hour time difference—yet I was eager.

It was the first day of the 2023 ESPKU conference. That’s the European Society for PKU and Allied Disorders Treated as Phenylketonuria.

Now, I knew why Birmingham was chosen as the location for the conference. But I was so busy planning my trip that I didn’t take time to reflect on its meaning.

I was in podcast recording mode. My plan was to interview as many people as possible. Which meant I had to make myself available whenever my guests were, and that meant I would miss most of the sessions.

But the first session… I had to hear it.

Professor Anne Green, author of the book Sheila: Unlocking the Treatment for PKU, shared the story of the first person ever treated for this rare disease.

I knew of Sheila, but honestly, most of my advocacy work has focused on either modern issues in the PKU community or the history, development, and current state of newborn screening.

I knew the names of Dr. Asbjorn Folling, who discovered PKU. Dr. Horst Bickel and the team at Birmingham Children’s Hospital, who developed the first treatment, and Dr. Robert Guthrie, who invented the bloodspot test for newborn screening. We who were present at the 2015 ESPKU conference in Berlin will never forget being in the presence of their descendants.

But Sheila Jones? I knew the name. Not the story.

And Mary Jones? I had never even heard her name until a few weeks before the event.

So, I stood in the back of the room, tired from jet lag, but eager to learn more about the history of my rare disease.

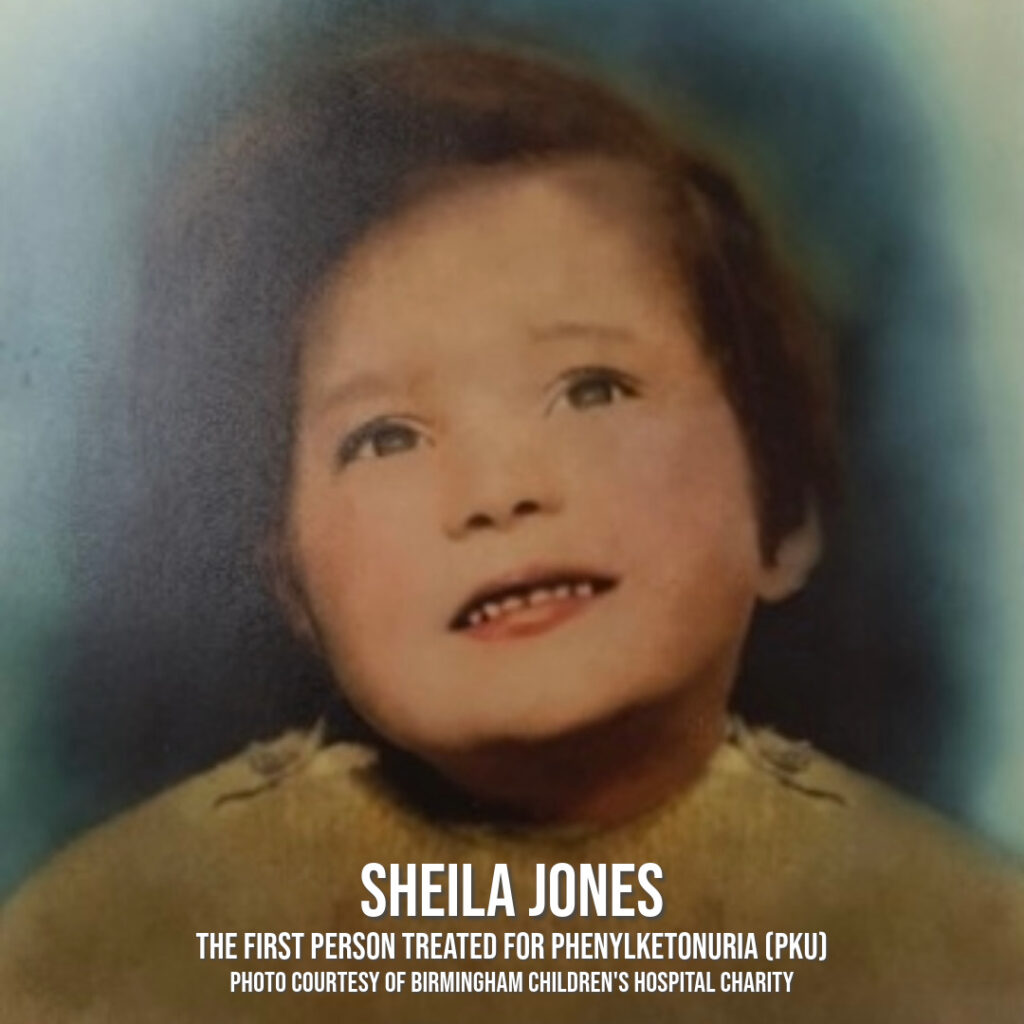

Sheila Jones

The Second World War was over, and life was returning to normal. In the United States, Harry Truman was president. Over in the United Kingdom, King George VI still reigned. Queen Elizabeth II ascended to the throne a few years later in 1952.

And the city of Birmingham was slowly recovering. It had suffered greatly during the war. Over 2,000 civilians died. Nearly 2,000 tons of bombs were dropped on the city.

It was in this world that a girl named Sheila was born, on October 1, 1949. She was the third child born to Mary Jones—her only daughter.

Mary had emigrated from Ireland and was alone in Birmingham. She lived in poverty, but did what she could to provide for her family. She was quiet by nature, but fierce when it came to her children.

And that fierce spirit—fighting for her family—is why the world will always remember her.

Because as Sheila grew, Mary could tell that something was wrong. Something was very wrong.

And she did not remain silent.

A Diagnostic Odyssey

Mary took Sheila to a family doctor who quickly recognized that she was developmentally delayed. The next step in their journey— a referral to Birmingham Children’s Hospital.

Initial tests indicated that Sheila might have PKU, so she was admitted to the hospital.

Yes, admitted to the hospital. This was a different time in the history of PKU.

Less than 20 years earlier, Dr. Asbjorn Folling discovered PKU. But there were few confirmed diagnosed individuals. In the world. The team at Birmingham Children’s Hospital was excited. They might have their first confirmed patient. They admitted Sheila to run more tests and confirmed what they suspected—Sheila had PKU.

It was now September 1951, and since Sheila’s diagnosis came so late, she was unable to sit for long periods, walk, or communicate verbally.

Her mother just wanted to know if they could do something to help her child. When Dr. Horst Bickel proudly confirmed Sheila’s diagnosis—excited to finally have a confirmed case of PKU—Mary had a different attitude: “It’s not fancy investigations I want, when are you going to treat my child?”

It’s easy to look back, decades later, and not understand the full weight of what was happening.

No treatment for PKU existed at the time. The idea of “dietary therapy”, which is the foundation of the modern PKU lifestyle, was untested. No one knew if early intervention would make a difference.

Over the years, much attention has been given to Dr. Horst Bickel. But, this was a team effort. Dr. John Gerrard, Dr. Evelyn Hickmans, and others at Birmingham Children’s Hospital all serve an important role in this story.

Because what came next changed everything for future generations of those with PKU.

Developing a Treatment for PKU

One difficult aspect of telling a story like this briefly, is that it’s hard to appreciate the time it took for these events to unfold.

The short version—The team at Birmingham Children’s Hospital thought that perhaps a phenylalanine-restricted diet would help Sheila. The idea had been considered by others. But this diet that we now know as the foundation of treatment for PKU, they made it happen.

And, at the Birmingham laboratory, they made and produced “Sheila’s special mixture”—the first metabolic formula for PKU, full of protein but without phenylalanine. So, a phenylalanine-restricted diet combined with a medical drink full of nutrients that Sheila needed.

This was an experiment. “Would it work?” “Would this help Sheila in any significant way?” First, they tried it while Sheila was admitted in the hospital. Then, after a few months, they sent her home, and Mary was left to manage this unusual routine, by herself. And consider how difficult this must have been since “Sheila’s special mixture” reportedly tasted, well, not pleasant.

Two paragraphs. I told this part of the story briefly, for a reason. Because from our perspective, we encounter Mary and Sheila’s story, learn about it, and then move on with our lives. And don’t appreciate what the family must have endured.

Because what I described above in two paragraphs, took place over two years. I can tell you this story briefly in this episode, but for the full understanding of what Mary, Sheila, and the rest of the family endured, I’ll direct you to Professor Green’s book.

Everyone currently living with PKU, and everyone taking care of them, knows how difficult this dietary therapy can be. But these days, we have each other to lean on for guidance and support.

Mary had no support. Sheila was the first person in the world receiving treatment for PKU. I can’t even imagine the burden Mary must have carried.

The sad truth is that while this discovery of dietary therapy for PKU was an important milestone, it didn’t change things long-term for Sheila. Her phenylalanine levels had improved, and so did her development and behavior, initially. Sheila’s experience with the diet had demonstrated clear benefits. But, due to her late diagnosis, again, it didn’t change things long-term.

Sheila continued with the diet at home for four years. But that was an incredible burden on Mary. She administered the diet while also caring for her other children, again, with no support, and through difficult circumstances. Eventually, Mary suspended the treatment at home. She could not sustain this burden by herself.

In the late 1950s, when Sheila was nine years old, she was admitted to an institution, Chelmsley Hospital, where she lived for the remainder of her life. And, for most of that time, lost to history.

Progress in PKU Treatment Since the 1950’s

Thirty years, that’s about how long Sheila was lost to history. The first person treated for PKU, and no one apart from the family knew where she was. Until 1987, that’s when her story re-emerged. Professor Green’s book explains how Sheila was re-discovered, and how her story began to be shared.

While life for Sheila went on at Chelmsley Hospital, and the effects of late-diagnosed PKU remained, developments for PKU treatment evolved.

In the 1960’s, newborn screening programs began to emerge around the world. The development of dietary therapy had proven to reduce phenylalanine levels. By implementing newborn screening practices, early intervention meant avoiding the most severe consequences of undiagnosed PKU.

Commercial sources of metabolic formula became available, and across the world a growing population of individuals with PKU were being born, screened, diagnosed, and receiving treatment. In the 1970’s and 80’s, children were removed from dietary therapy at various ages, the assumption being that the brain had fully developed enough for phenylalanine to no longer have adverse consequences.

But over the decades, debates ensued about whether dietary therapy should ever be suspended. Now, the concept of “diet for life” is the accepted practice.

Other treatments became available, at least in certain parts of the world. Today, access to existing treatments is one of the most pressing issues in the PKU community.

Despite the universal practice of dietary therapy, it is still difficult for some to get access to metabolic formula or to the specially created low-protein foods that became available over the years. And newer treatments that work for some are not available for all.

And, in my view, one of the most important developments—at least in my lifetime—is the emergence of a community of people affected by PKU. A real community. The rise of the internet made it easier to have contact with others. And now, social media has made that even easier.

As with all other rare diseases, daily life can include conversations with those who share your experience… who live anywhere in the world.

But for Mary Jones, there was no community. She was on her own. And that burden weighed heavily on her… and her family.

For Sheila, life remained the same at Chelmsley Hospital.

But both of them… Mary, through her relentless advocacy on behalf of her daughter… and Sheila, just through her presence in the world and what she endured as the first person with PKU to receive dietary therapy…

Both of them changed the world.

And the world will be forever grateful.

Mary and Sheila’s Legacy

That presentation at the ESPKU conference in Birmingham… it was the first time I encountered this story. Or, at least, slowed down long enough to think about it.

As someone who has PKU, it is easy to take things for granted… like the existence of newborn screening… or treatment for my rare disease.

But much of my advocacy work begins when I slow down long enough to reflect on what I’ve been given. And so… for the rest of that weekend, as I interviewed people in the PKU community from around the world, I thought about Mary and Sheila’s legacy.

We… are their legacy.

We… who were diagnosed through newborn screening at birth.

We… who have received treatment… the treatment that began with Sheila.

We… who make up the PKU community around the world.

And we… who are forever grateful.

Their legacy also continues in the amazing work being done by PKU organizations around the world.

And I want to highlight the work of the organization I’ve mentioned in this episode… the ESPKU.

It’s composed of member nations throughout Europe and elsewhere in the world. And the conference where this story began… hearing Mary and Sheila’s story… it’s an annual event—the highlight of the year.

It’s hosted in a different country each year, and in 2023 it was held in Birmingham because that’s where the treatment was developed.

In recent years the ESPKU has taken an extra step to honor Sheila, and her incredible sacrifice for the world.

There are many awards for professionals and scientists, but not always for patient advocates. So, the ESPKU created an award for people who help PKU patients. And it was named the Sheila Jones Award.

Individuals, groups of people, or organizations can be nominated, and those nominations are accepted from Rare Disease Day at the end of February to International PKU Day on June 28th.

The winner is decided by representatives of Birmingham Children’s Hospital and announced at the annual ESPKU conference. The award, which is a special trophy in the shape of a key, has been given six times with winners from Romania, Turkey, Croatia, Germany, and Ukraine.

For more information about the Sheila Jones Award, and to read about the nominating process, you can visit the ESPKU website.

That’s one way this incredible story has made a lasting impact on those affected by PKU. But Mary and Sheila’s legacy extends beyond the PKU community. Because they changed the world.

What happened in the early days of PKU history is an example of the possibilities for rare disease advocacy and treatment. One determined mother… did not remain silent, and spoke up for her child. She changed the world.

She never realized it in her lifetime, but her inability to be silenced determined the course of history for everyone living with PKU. And Sheila… she is the first of us. The first person diagnosed with PKU who was successfully treated, and although she could not communicate verbally, with her life she made ours possible.

The staff at Chelmsley Hospital had this to say about Sheila: “She was strong and could defend herself if there was something she didn’t want to do. She knew what she liked and what she didn’t like, and was a very determined lady.”

I understand that 95 percent of all rare diseases have no treatment. And sometimes, I wonder if the rest of the community wants to hear our story. We recognize that we are fortunate to have any treatment at all, and that’s something we never take for granted, even though our PKU community has different challenges.

May Mary and Sheila Jones serve as inspiration… Because it’s not just the leaders of nations that change history. Nor just the leaders of advocacy groups and organizations… It is ordinary people, like you and me, who can have a profound impact on this world.

Ordinary, determined people… One of Sheila’s brothers, Trevor Jones, said it best: “Sheila and Mum showed that it could be done.”

Rare Disease Advocacy Pioneers

Every day, with every choice, we are building a legacy. Mary Jones never knew the impact she had on the world. And while the story of Sheila was lost for decades, she was a pioneer rare disease patient. The first to receive treatment for Phenylketonuria.

Through Mary’s actions… her determination to find a treatment for her daughter… being the voice for her daughter who couldn’t communicate verbally…

And through Sheila’s life…

They changed the world.

Would any of us in the PKU community be here without them?

They changed the world for all of us.

Would I be able to use my voice and tell their story?

They changed the world for me.

And even as we fight every day for new treatments for PKU, and an eventual cure…

They are still changing the world for future generations.

Because their story shows us the way.

For parents living in isolation, fighting for a diagnosis for their child’s mystery illness.

For teens trying to fit in even when their rare disease makes them feel so very, very different.

For adults fighting every single day for access to their essential medications or treatments… that keep getting denied by those who don’t understand rare disease life.

No matter the struggle… no matter the action required…

With every advocacy project… with every legislative meeting… with every social media initiative…

You are changing the world, for yourself or for your child, and for future generations.

Mary and Sheila Jones…

Pioneers in the PKU community…

Pioneers in the global rare disease community.

And examples for us to follow…

As we never, never, never give up.

Leave a Reply