In my latest episode, “Call Me Bob,” I delve into the life and legacy of Dr. Robert Guthrie, a pioneering figure in newborn screening. Guthrie’s groundbreaking work in developing the bloodspot test for newborn screening has saved countless lives and continues to impact the world today. Join me as I share his story, the personal connections I’ve made with his family, and the profound lessons I’ve learned from his dedication to ensuring every baby gets a fair chance at life. Read on to discover how one person’s relentless passion can change the world.

Call Me Bob – A Story About Dr Robert Guthrie

There’s an idea I’ve explored all throughout this season: that one person can make a difference. It’s not a question I’m asking. I’m not seeking an answer. I do that a lot on this show—ask questions about life. Explore difficult themes we tend to avoid in our daily lives.

But this question is answered… at least for me. I believe—passionately—that one person can make a difference. That one person can change the world for someone.

But every now and then there are people who come along and shine so brightly that their legacy endures. And they change the world.

Today I want to tell you about one such person. We never met, although I’ve met some of his family. He was born in the early 1900s, just a couple of years after my grandfather. I didn’t get to know either of my grandfathers. One passed away before I was born and the other when I was five. Maybe this is why I’m so drawn to stories from that generation. It’s my way of trying to understand the world they lived in.

And it’s a world vastly different from ours. A world in which no treatment for PKU existed. A world in which newborns weren’t screened for some rare diseases like they are today—or at least the way they should be.

A world without a rare disease community because society had not yet decided to stand up for people like you and me.

It was in a world like this that one person was born. Someone who refused to give up on the idea that every baby deserves a fair chance at life.

And his name was Bob.

A Quick Word about Newborn Screening

Each year nearly four million US newborns are screened for a panel of genetic conditions, hearing loss, and critical congenital heart disease or CCHD as part of a process called “newborn screening.” Fourteen thousand of those babies will be identified with a condition that could cause disability or death if not detected and treated early. That’s 14,000 babies whose lives are saved or improved through newborn screening every year. It is one of the fastest, safest ways to help protect your baby against certain medical conditions.

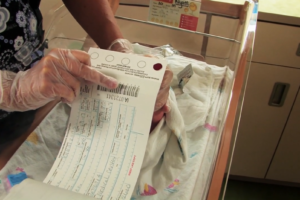

Newborn screening has three components: hearing, CCHD, and blood spot screening. Hearing and CCHD screening are conducted at the hospital before the family is discharged (or at home before the birth attendant leaves), but the blood spot screening is conducted by the state or territorial public health laboratory. A day or two after the baby is born, a few drops of blood are collected from the baby’s heel on a filter paper. It’s a simple and routine procedure. The sample is then sent to the public health laboratory which tests for a panel of genetic conditions that may differ state to state. Those little drops of blood can provide huge amounts of life-altering information in the baby’s first days of life.

But public health labs do more than newborn screening! Whether it’s diagnostic and surveillance testing for infectious diseases, tracing the source of a foodborne outbreak, or testing the air, water, and soil for contaminants, your public health lab is there working to keep you and your community healthy.

And there’s an organization that supports public health laboratories in the US and many overseas called the Association of Public Health Laboratories or APHL. APHL works to strengthen the role of public health labs to make sure they have the resources they need to do their jobs. APHL works closely with local, state, federal, and global partners to ensure routine testing is performed consistently and accurately and that public health emergencies are responded to rapidly and effectively. To learn more about APHL and public health laboratories, visit APHL.org.

Meeting the Family of a Newborn Screening Legend

“Newborn screening saves lives.” I say that often. But there was a time when I never thought about newborn screening. I took it for granted.

But early in my advocacy journey, I began receiving messages from those who work in the field of newborn screening. When people typically think of newborn screening, they think of babies. But as an adult living with PKU, I was eager to share my perspective.

Through these connections and friendships, I connected with the team at the Association of Public Health Laboratories or APHL. We partnered on an advocacy campaign in 2013—the 50th anniversary of newborn screening in the United States. A campaign that culminated in an advocacy event on Capitol Hill in Washington DC.

I produced a video for the event, spoke on a panel of newborn screening advocates, and met so many people affected by newborn screening. But that night someone spoke and her story moved me.

Her name was Patricia Guthrie and she told us about her father, Dr. Robert Guthrie.

Photos from a newborn screening advocacy event hosted by the Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL) on Capitol Hill in 2013. I spoke on a panel of other newborn screening advocates, moderated by Dr. Richard Besser (then with ABC News). And I met Patricia Guthrie, daughter of Dr. Robert Guthrie, and we became friends. For more information about her father, please visit the Robert Guthrie Legacy Project.)

Public vs. Private Personas

Throughout this season I have tried to be subtle about it but now I’ll state it plainly. I love history. It’s not about dates, facts, and figures. Those are important but to me not the essence of history.

History is the study of people. It’s a story.

I have many interests and if I could live a thousand lifetimes or take a trip to an alternate reality in one of them, I would like to have been a history professor.

I wasn’t always like this but I’m the person who can spend all day in a coffee shop with a good book and be perfectly content. Because when I’m focused on a story—whether reading one or telling one—it’s like everything else disappears. And I get focused—laser-focused.

Because people are endlessly fascinating. It’s the reason I’m a storyteller. There’s always a story to tell because there’s always a person to meet.

I feel like in a small way I’ve met Dr. Guthrie. Not in a real sense of course. I’m not trying to overstate things. But in the same way you feel like you know your favorite actor, author, or musician.

Something about their soul reaches through time and space and captivates your heart and mind.

I feel like I’ve met him because I met his daughter Patricia—or Patty—and we became friends. I’ve had dinner with her and some of the family. And heard stories not just about “Dr. Robert Guthrie”… but about their dad, Bob.

Often we put people on pedestals. We treat them as if they are more than human because of their accomplishments. We call them heroes, revere them but forget that they are still people. I’m fascinated by this duality—someone’s public persona and their private self.

In this case, I’m fascinated by two sides of the same person…

Dr. Robert Guthrie, “Father of Newborn Screening”…

And Bob, Patty’s dad.

Photo courtesy of the Robert Guthrie Legacy Project

Dr. Robert Guthrie

Dr. Robert Guthrie was a research microbiologist with an MD and PhD. It was the birth of his second child, John, that took his life in a different direction.

His son was developmentally delayed. And thus began one family’s “diagnostic odyssey,” an experience families today in the rare disease community know all too well.

Guthrie devoted his personal and professional life to change things for other children like his son. He was an advocate but also a scientist. At one point he met a physician treating people with phenylketonuria or PKU.

Recent research had shown that a low-protein diet could improve their lives but required constant monitoring of the level of the amino acid phenylalanine in their blood. And the physician needed a simpler tool for that. So Guthrie created one.

But in 1961 his niece was diagnosed with PKU—a late diagnosis. An idea formed: Can’t we do something to diagnose children sooner?

And so began a lifelong determination to do whatever he could to prevent the consequences of undiagnosed or late-diagnosed PKU. He believed—passionately—that every baby deserves to be screened for PKU and other rare diseases.

Every baby. Across the world.

Period.

His invention, the bloodspot test, was remarkably simple—a drop of blood from a newborn blotted onto filter paper which then could be analyzed to determine the phenylalanine levels in the blood and therefore detect and diagnose PKU. The basic concept has been applied to other rare diseases.

In 1963 Massachusetts became the first US state to implement newborn screening for PKU. But his work wasn’t done.

Dr. Guthrie spent the rest of his life working to expand newborn screening across the world.

Because again… every baby deserves to be screened.

Photo courtesy of the Robert Guthrie Legacy Project

Bob

That’s a little bit about Dr. Robert Guthrie. But what about Bob?

He was… eccentric. Researchers who knew him describe someone who was so driven that he would get wrapped up in his thoughts, lose track of time, and call with ideas—in the middle of the night!

He was… a sailor. He may not have been a great one but he loved to sail. His favorite phrase, something he wished for his friends all the time, and how he ended all his letters: “Fair winds!”

He was… contradictory. A research microbiologist—an accomplished scientist—who almost failed anatomy class in medical school (because he didn’t like the bodies and body parts) and organic chemistry (because he was more interested in the woman who sat next to him).

He was… pragmatic. He loved going to events where you had to wear a name tag… because he thought you should always wear a name tag. It just made sense to be able to look down and see someone’s name. And he didn’t care about titles. He would tell anyone “Call me Bob.”

He was… a father. He would take the family on his newborn screening advocacy adventures when he could. When he couldn’t he’d always return with a photo slideshow. But not with photos of the sights he saw as a tourist but of his work of course. Although, Patty did mention that he loved the view looking out an airplane window and always had plenty of those photos to show.

He was… a human.

Dr. Robert Guthrie – A Legacy that Endures

But what is he… to me? And why am I telling you about him?

He is an example and a reminder that one person can make a difference.

One person can change the world.

One person can change history.

What began with a simple test created in Buffalo, New York, became a public health program across the United States. It then spread throughout the world.

According to the National Institutes of Health or NIH, more than 40 million babies across the world receive a newborn screening bloodspot test each year. What began with a test for PKU now includes other rare diseases. And yet the work continues to ensure that every baby born in the world receives timely, accurate, and comprehensive newborn screening.

So I continually return to the example set by Dr. Robert Guthrie… and by Bob.

Allow every part of yourself—your professional identity and your personality—to become so consumed by an idea that you will never stop.

Not as long as one baby still needs to be screened. Or one rare disease added to the newborn screening panel.

Dr. Robert Guthrie… Bob… became so driven by an idea that he saved countless lives.

A Day to Remember Dr. Robert Guthrie

Before I continue, Dr. Guthrie’s birthday is on June 28th and in honor of that, I want to share something with you. International Neonatal Screening Day is celebrated on the 28th, a day to raise awareness of the importance of neonatal screening or newborn screening and its critical role in providing early diagnosis for certain rare diseases and saving lives. Visit neonatalscreeningday.org for more info.

But I think it’s important to remember that newborn screening is just the first step in the complex medical care required by those who receive an early diagnosis because of this public health program.

The PKU community also celebrates this day as International PKU Day. Established by the ESPKU or European Society for PKU and Allied Disorders Treated as Phenylketonuria, it’s a day when we raise awareness of the first rare disease detected through newborn screening. Visit espku.org for more information on International PKU Day.

And this year, 2024, the ESPKU is specifically raising awareness of issues affecting adults living with PKU. Because there are many issues facing our community: the difficulty of dietary therapy, access to treatment, financial barriers, mental health, long-term effects of high phenylalanine levels.

Newborn screening saves lives. That is absolutely true and I say it all the time. But it’s just the first step.

If society is going to screen babies for rare diseases—and we should—then let’s also work to create a world where those babies can grow up into healthy adults.

These are issues affecting the PKU community. If you’re affected by another rare disease, please let me know what issues are affecting your community. And how I can help you raise awareness of what matters to you. And let’s work to create a better world—for all of us.

A Final Word

While writing this story, I reached out to Patricia Guthrie—Patty—and we had a conversation about her dad and his legacy.

She remembered the moment when she finally understood who her father truly was. It was 1993 and she was at a meeting of the newly created New England Connection for PKU and Allied Disorders or NECPAD. It’s one of the regional support groups here in the US for individuals and families affected by PKU and other metabolic disorders.

She heard adults with PKU describe their experiences. She heard parents talk about how great their children were doing. And at one point, someone came up to her, hugged her, and said “I love your father. He saved my grandchild.” Patty said “It sunk in finally what he had been doing all those years.”

I first met Patty in 2013 at that newborn screening event in Washington DC that I mentioned at the beginning of the story. And we became friends. We’ve seen each other a lot over the years at other events. I interviewed her for a video while at an event and she had this to say about her father: “He wasn’t around much when I was growing up but he was saving the world.”

Yes, he was.

I say this a lot: “Newborn screening saves lives. It saved mine.”

But I’ll make it even more personal. Dr. Robert Guthrie… Bob… he saved me. And he saved my friends.

I’ll end by sharing this… there’s a reason I’m passionate and driven when it comes to newborn screening and it’s not just because I have PKU.

I share stories about my experiences in TV photojournalism on this podcast. Just a couple of episodes ago during this season I shared a story I remember every day about a child who suffered a tragedy. There are other stories involving children that I covered that I’ll never talk about.

Let’s just say that some tragedies are accidents and some the result of atrocities and as much as we want, we can’t stop them.

But some things we can stop.

We can prevent the worst outcomes from undiagnosed phenylketonuria. Or maple syrup urine disease. Or homocystinuria. Or tyrosinemia. Or many, many others that are on the newborn screening panel.

So we fight.

We fight to make sure that newborn screening occurs and a diagnosis confirmed in a timely manner so that a child doesn’t suffer consequences—or die—because of a delayed diagnosis.

We fight to make sure that the results are accurate so that no one slips through cracks in the system.

And we fight so that screening is comprehensive and that more rare diseases are added to newborn screening programs.

Timely. Accurate. Comprehensive. That is the standard.

And so… we fight.

And we will never, never, never give up.

2 Comments

Leave your reply.